When you switch on your television and tune in to a news channel these days, all you hear about the Pakistani economy is that it is in a free fall. Without a doubt, the economy has faced several challenges historically. In the recent past, Pakistan’s economic difficulties appeared to be even more difficult to resolve than the country’s political, ethnic, and regional disputes, and the successive administrations’ lack of attention to economic matters added to the atmosphere of crises (Hussain 9). Though much has been written in the press and journals about the economic tension in Pakistan, positive indicators have been almost entirely overlooked. In contrast to other regional players and its own history, Pakistan’s growth has been copacetic during the last five years. High growth in income and exports, efforts for effective debt management and increasing foreign reserves for the economy have diminished the crisis Pakistan has faced since the last three decades (Pakistan Economic Survey 2020-21). Although there is still much work to be done, the process of restructuring Pakistan’s economy into a stronger one has begun. “Pakistan’s economy is on the path to recovery, supported by promising growth in the industry and services sectors,” said Asian Development Banks’s (ADB) Country Director for Pakistan Yong Ye. Thus, with a plethora of glaring opportunities and vast economic potential, Pakistan is open for business. More efficient policymaking along with constitutional power transfers, a decrease in civil unrest and terrorism, and other successful responses to economic tragedies in the twenty-first century have all set Pakistan’s economy on the right track to recovery.

During the 1960s and 1980s, when India was stuck with its Hindu rate of development, Pakistan’s economy witnessed extraordinarily high rates of growth (Khanna 39). An example of the booming Pakistani economy of the 90s is that in the year 1995, Pakistan’s exports were higher than the combined exports of South Korea, Turkey, and Indonesia (Khanna 40). The GDP was growing at a rapid rate and the newly emerged country was on its way to become a serious regional power. To outsiders, Pakistan had been a model developing economy (Hussain 12). However, Pakistan’s economic fiasco has been exacerbated by sociopolitical factors since, and it’s difficult to assess how far the country has come out of it. The tribulation started when in 1971 the eastern half of the country was cut off after a separatist war which left Pakistan’s economy in a miserable condition. The secession of the eastern wing robbed the western wing of a large internal market (Khanna 42). Since intra-wing exports were such a large part of Pakistan’s economy, after the war, the country faced the severe challenge of finding a new market.

Since the death of Zia-ul-Haq in 1988, the socio-economic turmoil in Pakistan has been growing. The Pakistani elite and the state have found it difficult, partly due to alternating civil and military regimes, to forge a cohesive and stable economic policy for the country and thus the economy has lurched from one crisis to another. Pakistan’s growth and development have been hampered by a lack of consistent policy (Saboor et al.). Bangladesh, which was previously Pakistan’s impoverished eastern half, is well ahead of Pakistan in major economic measures, demonstrating how Pakistan has fallen behind in its economic race. Its GDP per capita of $1,855 in 2019 was a third more than Pakistan’s $1,284 as the two nations’ growth and human development paths diverged dramatically (Siddique). From 1960 to 2006, India, Pakistan’s archrival on the eastern border, was just richer than Pakistan for five years (World Bank). Pakistan’s GDP per capita was 1.54 times that of India in 1970. Considering exchange rate basis, India’s per capita income in 2020 was 1.56 times that of Pakistan, with an all-time high of 1.63 times in 2019. (Statistics Times). Showing how two countries that got independence at the same time and have a comparable cultural and resource base, now have vastly distinct economic prospects.

Domestic political conflicts and policy lapses in the past resulted in long-term macroeconomic imbalances, however, the Pakistani economy has begun to recover in the past demi-decade. For the last decade and a half, Pakistan has experienced peaceful power transfers between democratically elected leaders, which has aided the country’s development. As a result, Pakistan’s economy has benefited from the implementation of sound economic policies and a stable fiscal policy framework. The policy framework in the recent past that has been more focused towards solving structural problems. A structural problem from the past was that a lot of money was tied in non-productive markets, the problem was that none of the governments had the vision to focus on increasing the real wealth of the nation. However, recent administrations have formed a more conducive environment for productive setups. As a result, the business environment in Pakistan has improved. Due to the relative ease of doing business now, Pakistan’s information technology exports increased by 47% from July to May in fiscal year 2020-21, reaching $1.9 billion according to the State Bank of Pakistan (Khan et al.).

Furthermore, the textile industry, which was on the verge of collapse in the past and was relocating to Bangladesh as investment in Pakistan became too perilous due to poor policies and domestic conflicts, has been rescued, and Pakistan has registered its highest-ever textile exports of $14.24 billion during the first nine months of FY22 (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics). Despite stringent fiscal limitations, the government’s prompt and appropriate policy initiatives resulted in a swift revival of this industry. “The textile sector has substantially increased its capacity to produce the value added and finished products which will further increase by 20 percent by the end of current fiscal year 2021-22”, said Secretary General and Executive Director of All Pakistan Textile Association, Shahid Sattar (Mustafa).This is a crucial sign for Pakistan’s economic recovery since the textile sector employs a large portion of the population and sources its raw materials from the country’s agriculture industry, thus an increase in textile exports benefits the whole economy.

Fiscal incentives and policies aimed at improving export competitiveness, improving industrial performance, and increasing private investment have all helped improve the economy’s outlook in the past five years. Moreover, policies for sustainable and inclusive economic growth have played a key role in creating a vibrant Pakistani economy. Economic growth is projected to recover to 4.2 percent in FY24, according to the World Bank, thanks to structural improvements that will promote macroeconomic stability. Better international relations and supportive policies for domestic manufacturers have also improved Pakistan’s economic outlook. In 2017, for example, China invested billions of dollars in Pakistan’s energy and infrastructure, and the World Bank applauded Islamabad for increasing GDP growth, which surpassed 5% for the first time in over a decade that fiscal year (Rizvi).

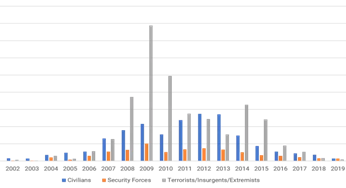

One of the most critical reasons for Pakistan’s economic stagnation was terrorism. Terrorism has been the main challenge to the country’s growth and development (Shahbaz et al.). Aside from the intangible loss of human life, other major economic costs of terrorism include capital flight, poverty, infrastructure destruction, a reduction in exports and foreign direct investment (FDI), a shift in development spending to law-and-order maintenance, and low public revenues among other things (Hyder et al.). The previous governments struggled to overcome the menace of terrorism in the country. Thus, terrorism has been the biggest impediment for Pakistan’s economic growth in the previous two decades. It is also worth noting that terrorism has had a nocuous effect on GDP growth in Pakistan, whereas India, a comparable economy, has managed to overcome the effects of terrorism on its GDP (Zakaria et al.). Today, however, Pakistan’s dark days seem to be over, and a reduction in terrorism has restored confidence in the country’s economy, which had been nonexistent for the preceding two decades. Terrorism in Pakistan began to decline in the years following 2013, as shown in the graph by Madiha Afzal of Brookings. The sharp decline in the blue line in the graph depicting civilian casualties began around the year 2013, and there was a significant decline in overall terrorism activities after 2015, which is precisely when the Pakistani economy began its upward trajectory.

Fig. 1. “Yearly Fatalities.” SATP, www.satp.org/datasheet-terrorist-attack/fatalities/pakistan.

Foreign investment in Pakistan has soared as confidence has risen. Not just individual investors, but also foreign countries have invested heavily in Pakistan. This surge in foreign direct investment (FDI) has had a significant economic impact. FDI boosts income levels and creates job possibilities in the host nation, boosting overall economic growth (Javaid). The start-up culture in Pakistan is growing as a result of the decline in terrorism and the rise in investor confidence. According to invest2inovate (a Pakistani consultancy firm) 83 startups raised $350m in 2021 alone (Chughtai). This massive infusion of capital into Pakistan’s developing economy bodes well for the country as it ensures organic economic growth while also creating wealth in the country. This has occurred in other parts of the world as well, and the venture-backed start-up transformation that occurred in the United States, China, India, and Indonesia is now gaining traction in Pakistan. Furthermore, two Pakistani firms have made it to Forbes’ ‘Asia’s Best Under a Billion 2020’ list, demonstrating the country’s tremendous growth because of reduced civil unrest and terrorism (The Daily Dawn). Aside from that, Pakistan’s auto industry is at an all-time high. Previously dominated by only three manufacturers, the new auto policy (2016-2022) and more secure business climate have attracted new players to the market, increasing the auto sector’s contribution to GDP. Furthermore, according to a survey conducted by the overseas investment chamber of commerce and industries (OICCI), 68% of the companies operating in Pakistan expect their profitability to rise in the next two years (News Desk). According to another survey conducted by (OICCI), consisting of 10 regional countries, Pakistan has a better investment climate compared to six countries in the survey. Moreover, due to a drastic fall in terrorism, continued improvement in community mobility and expansionary fiscal policy, private consumption has strengthened in Pakistan.

For some years now, it has been clear that Pakistan’s debt burden is highly onerous and despite the critical need of analyzing our debt crisis and establishing a strategy to deal with it, little systematic work on debt issues has been done in the past. Debt management, much like economic management, is an art rather than a science. Pakistan has been trapped in this debt quagmire for very long. During Zia’s 11-year tenure (1977–88), the state debt increased sixfold, demonstrating enormous and rising budgetary deficits (Gul). During this time, the debt expanded at an average yearly pace of 17.7 percent in nominal terms and over 10% in real terms (Hassan 436). Historically the debt burden has been exacerbated by elected officials’ incompetence, a weakening economy, and, most important, a significant decline in real revenue growth. Just before Khan’s regime was overthrown through a no-confidence motion, the government and the opposition were trading barbs in the Senate and the national assembly over increasing external debt, with the opposition chastising the administration for establishing a new record. However, there is a little understanding of how the debt problem is being addressed. According to the government of Pakistan’s ministry of finance, the country recorded exceptionally high tax collection as government revenues in Pakistan increased to 6903.40 PKR Billion in 2021. This extraordinary increase in revenue is being utilized to pay down debt. In the previous fiscal year, Pakistan spent Rs. 85 out of Rs. 100 on debt repayment, while India’s federal government spent Rs. 51 and Bangladesh spent roughly Rs. 20 out of total tax and non-tax revenues (Khattak). Aside from the prompt repayments, Pakistan’s overall debt to GDP ratio has improved, falling from 87.6 percent to 83.50 percent in a year (Haroon). This year’s decrease in the debt-to-GDP ratio indicates that the government is concerned about the mounting debt problem and is developing strategies to address it in the long run, such as increased reliance on foreign remittances and reduction in import bills. Furthermore, acquiring additional debt for Pakistan is not a big concern, contrary to what many people believe. The world’s most powerful economy, the United States, has a debt-to-GDP ratio of 133 percent, while Pakistan’s stands at around 83 percent. The only catch is that the debt must be managed effectively.

Many people in Pakistan are skeptical of such an optimistic economic outlook, which does not reflect the reality of their situation, since the economy’s two primary concerns at the time, sky-high inflation, and the depreciation of the Pakistani rupee, have made life difficult for the general populace. Opposition parties flocked to the streets in several cities across Pakistan during the previous government’s tenure, which has recently expired, in protest of the country’s rising inflation. Inflation had become such a significant problem in the country that Shahbaz Sharif, then the Leader of the Opposition in the National Assembly and President of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), appealed to the people and invited them to join a demonstration against rising inflation. He claimed that providing the government more time means the people of the country would suffer higher inflation and unemployment (Javaid). However, one thing to keep in mind is that inflation is now a global phenomenon, and no country has yet worked a way to avoid it. Inflation has come back faster, spiked more markedly, and proved to be more stubborn and persistent (Reinhart). Rising oil prices and a supply chain crisis are at the basis of this global inflationary pressure. In Pakistan, this pressure is felt more acutely since the energy industry accounts for Pakistan’s largest import bill. In October, Pakistan’s overall energy cost was roughly $1.6 billion, including $0.7 billion in petroleum imports, including motor spirit, high-speed diesel, and furnace oil (Kiani). Moreover, While the currency reserves are at their peak, the rupee continues its losing streak as the State bank has refrained from intervening in the forex market to artificially buoy the currency (Rizvi). With only a month’s import bill putting a large dent in foreign exchange reserves, the rupee’s depreciation is inevitable. These shocks, along with the fact that the economy is largely reliant on imports, have pushed inflation to an all-time high. However, the negative impact of inflation will be minimized as new monetary regulations such as higher policy rates and efforts to reduce liquidity in the economy are being implemented (Najeeb). Another topic that has been widely criticized is relief packages, particularly by recent administration of Pakistan-Tehreek-Insaaf (PTI). In response to Ex-Prime Minister Imran Khan’s announcement of a relief package, Zubair, a leader of PMLN and former governor Sindh, stated that the discount granted to the public must be paid for by someone.” In the end, the government will fund it by raising taxes, taking on more debt, or printing more notes, all of which would raise inflation,” he said. One thing to note is that the government has not increased Pakistan’s budget deficit or obtained additional loans to fund the relief packages; rather, as former finance minister Shaukat Tareen stated, the relief packages have been funded entirely through a record increase in revenue and unused dividends from state-owned enterprises (Profit).

Effective tackling of strategic economic problems in Pakistan has contributed to the growth of the economy. Fiscal incentives and policies to promote export competitiveness, improve the performance of the manufacturing sector, and increase private investment have continued to play an important role in improving the country’s economic outlook. The proactive policy measures by the government and State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) incentivized the use of formal channels and as a result foreign remittance is also at an all-time high. During the first quarter of the previous fiscal year, overseas Pakistanis contributed the highest-ever $8 billion in remittances, a 12.5 percent jump over the same period the previous year (Iqbal). Double-digit growth in remittances helped to finance the trade deficit. Pakistan’s exports are on the rise as the country progresses away from dwindling competitiveness. As a result, the country’s current account deficit (CAD) shrank by 78.46 percent to $545 million in February from a whopping $2.531 billion (The Daily Dawn).

For the previous half-decade, Pakistan’s economic situation in several sectors has been critical in overcoming the menace of poverty and unemployment. Pakistan’s economy created 5.5 million jobs during the past three years –on an average 1.84 million jobs a year, reveals findings of Labour Force Survey (LFS) published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS). This is far higher than the yearly average of creation of new jobs during the 2008-18 decade (Rana). It may come as a surprise for some, but now Pakistan is the country with the lowest unemployment rate in the entire region. According to the findings, 4.3 percent of Pakistanis were unemployed, while regional rival and immediate neighbor India had the highest unemployment rate at 8%. Maldives’ unemployment rate was found to be 6.3% and Sri Lanka’s 5.9% (News Desk Express Tribune). Poverty assessed at the lower-middle-income class poverty line is also on the decline, thanks to the economic recovery and improving labour market conditions.

In a world full of constant economic shocks, Pakistan’s booming Information Technology (IT) sector is turning out to be a silver lining for the country. It is critical to discuss this sector of the economy since it has contributed significantly to India’s, China’s, and the United States’ economic growth. According to the State Bank of Pakistan, information technology exports of Pakistan have now hit $1.9 billion mark (The News). This industry has boosted the country’s startup and entrepreneurial culture. Fine green shots are emerging, notably in the burgeoning technology and startup sector, and the government has thus far played a positive role in ensuring this. In the last year, the number of Pakistani start-up companies skyrocketed as more and more tech-savvy entrepreneurs seek to utilize technology to solve long-standing business problems (Khan). The IT industry is a vital component of any economy in the twenty-first century, and it is much more significant in Pakistan, where freelancing and IT-based start-up firms are crucial for generating output from the country’s vast youth population. The world economy has also recently gone through a tragic period of covid-19, however, in that period, Pakistan’s expansion of the national cash transfer program, accommodative macroeconomic policies, and supportive measures for the financial sector, all helped mitigate the adverse effects of the economic crises (World Bank). According to the Asian Development Outlook (ADO) 2021 Update, the ADB’s annual flagship economic report, Pakistan’s economy is likely to continue to rebound in FY2022, backed by increased private investment, rising business activity, and economic stimulus measures.

Answering Pakistan’s economic conundrum can never be in binary terms; however, clear indications of a prospering economy make us optimistic about the economic future of the country. Although there is still an uphill struggle for Islamabad, the economy is growing at a rapid rate and the recent developments show a positive indication for the economy. Pakistan’s decision-making brass’s turn towards democratic norms in the previous decade, a dramatic drop in terrorism and civil turmoil, and a burgeoning tech-startup culture have all aided the country’s progress. Although the country’s economic issues persist, the extremely encouraging data suggest that Pakistan is far from any disastrous economic crisis that countries like Sri Lanka and Lebanon have experienced recently. The rise in economic confidence and the massive infusion of foreign capital into Pakistan imply that the country’s economy is heading towards a promising future. If things keep going in this direction, Pakistan’s economy will soon be hailed as a shining example of tenacity, success, and long-term progress across the world.

Works Cited

Afzal, Madiha. “Terrorism in Pakistan Has Declined, but the Underlying Roots of Extremism Remain.” Brookings, Brookings, 9 Mar. 2022, www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/01/15/terrorism-in-pakistan-has-declined-but-the-underlying-roots-of-extremism-remain/.

Asian Development Bank. “Pakistan’s Economic Recovery to Continue amid Steady Vaccine Rollout – ADB.” Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, 22 Sept. 2021, www.adb.org/news/pakistan-economic-recovery-continue-amid-steady-vaccine-rollout-adb.

Chughtai, Alia. “Pakistan’s Startups Take Centre Stage.” Infographic | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 16 Mar. 2022, www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/3/16/pakistans-startups-take-center-stage.

Gul. Pakistan’s Public Debt: The Shocks and Aftershocks, 3 Nov. 2008.

Haider, Mehtab. “Out of Total Revenue Last Fiscal Year, Pakistan Spent RS85 out of 100 in Debt Servicing.” Thenews, The News International, 27 Nov. 2021, www.thenews.com.pk/print/912063-out-of-total-revenue-last-fiscal-year-pakistan-spent-rs85-out-of-100-in-debt-servicing.

Haroon, Aleena. “Pakistan’s Debt Has Increased by 11.5% over Last Year.” Pakistan’s Debt Has Increased by 11.5% Over Last Year, ProPakistani, 6 Oct. 2021, propakistani.pk/2021/10/06/pakistans-overall-debt-jumps-11-5-yoy-in-august/#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20positive%20development%20is,GDP%20from%2056%25%20last%20year.

Hassan, Parvez. “The Pakistan Development Review.” Winter 1999,Vol. 38, No.4 Part I, 1999, thepdr.pk/pdr/index.php/pdr/issue/view/155.

Hussain, Ishrat. The Role of Politics in Pakistan’s Economy – JSTOR. Journal of International Affairs Editorial Board, 2009, www.jstor.org/stable/24384169.

Hyder, S., Akram, N., & Padda, I. U. H. J. P. B. R. (2015). Impact of terrorism on economic development in Pakistan. Pakistan Business Review, 839(1), 704–722.

Iftikhar, Parvez. “Pakistan and the Digital Economy: Future … – Jstor.org.” J Store, Sustainable Development Policy Institute, 1 Jan. 2019, www.jstor.org/stable/resrep24393.16.

Iqbal, Shahid. “Pakistan Gets Record $8bn Remittances in July-Sept.” DAWN.COM, 9 Oct. 2021, www.dawn.com/news/1650949#:~:text=KARACHI%3A%20Overseas%20Pakistanis%20sent%20the,the%20same%20period%20last%20year.

Javaid, Rana. “Opposition Launches Protests against Inflation in Various Cities Today.” Geo.tv: Latest News Breaking Pakistan, World, Live Videos, Geo News, 22 Oct. 2021, www.geo.tv/latest/377411-opposition-launches-protests-against-inflation-in-various-cities-today.

Javaid, Waqas. “FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT IN PAKISTAN.” Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Economic Growth of Pakistan-, Södertörns Högskola | Department of Economics, n.d.

Khan, Mutaher, and Khurram Zia Khan. “The Rise of Pakistani Tech.” DAWN.COM, 19 Sept. 2021, www.dawn.com/news/1647193.

Khanna, Sushil. Growth and Crisis in Pakistan’s Economy – JSTOR. Economic and Political Weekely, 24 Dec. 2010, www.jstor.org/stable/25764241.

Khattak, Marwa. “Pakistan Spent Rs. 85 out of 100 in Debt Repayment; Total Debt and Liabilities Crossed Rs. 50.5 Trillion Mark.” Startup Pakistan, 29 Nov. 2021, startuppakistan.com.pk/pakistan-spent-rs-85-out-of-100-in-debt-repayment-total-debt-and-liabilities-crossed-rs-50-5-trillion-mark-2/#:~:text=85%20out%20of%20100%20in,50.5%20trillion%20mark%20%E2%80%93%20Startup%20Pakistan.

Kiani, Khaleeq. “Another Energy-Expensive Year.” DAWN.COM, 3 Jan. 2022, www.dawn.com/news/1667260.

Mustafa, Khalid. “Pakistan’s Textile Industry Starts New Fiscal Year with a Bang as Exports Surge by 17%.” Geo.tv: Latest News Breaking Pakistan, World, Live Videos, Geo News, 27 Aug. 2021, www.geo.tv/latest/367329-pakistans-textile-industry-starts-new-fiscal-year-with-a-bang-as-exports-surge.

Najeeb, Dr Khaqan Hassan. “Managing Pakistan’s Inflation.” Thenews, The News International, 8 Mar. 2022, www.thenews.com.pk/print/939657-managing-pakistan-s-inflation.

“Overview.” World Bank, 8 Apr. 2022, www.worldbank.org/en/country/pakistan/overview#1.

“Overview.” World Bank, 8 Apr. 2022, www.worldbank.org/en/country/pakistan/overview#1.

“Pakistan’s Economy Created 5.5 Million Jobs in Last 3 Years.” Pakistan Today, 31 Mar. 2022, www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2022/03/31/pakistans-economy-created-5-5-million-jobs-in-last-3-years/.

“Pakistan’s Economy Moving in the Right Direction, Says Tarin.” Profit by Pakistan Today, 9 Mar. 2022, profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2022/03/09/pakistans-economy-moving-in-the-right-direction-says-tarin/.

Rana, Shahbaz. “Employment Boom in Last 3 Years.” The Express Tribune, 31 Mar. 2022, tribune.com.pk/story/2350416/employment-boom-in-last-3-years.

Reinhart, Carmen. “The Return of Global Inflation.” World Bank Blogs, 14 Feb. 2022, blogs.worldbank.org/voices/return-global-inflation.

Rizvi, Syed Zain Abbas. “The Economic Conundrum of Pakistan.” Modern Diplomacy, 15 Sept. 2021, moderndiplomacy.eu/2021/09/16/the-economic-conundrum-of-pakistan/.

Saboor, A., Khan, A. U., Hussain, A., Ali, I., & Mahmood, K. (2015). Multidimensional deprivations in Pakistan: Regional variations and temporal shifts. The Quarterly Review of Economics, 56, 57–67

Shahbaz, M., Shabbir, M. S., Malik, M. N., & Wolters, M. E. (2013). An analysis of a causal relationship between economic growth and terrorism in Pakistan. Economic Modelling, 35, 21–29.

Siddique, Abubakar. “How Pakistan’s Economy Is Failing Its People.” RFE/RL, How Pakistan’s Economy Is Failing Its People, 25 May 2021, gandhara.rferl.org/a/pakistan-failing-economy/31272373.html.

Zakaria, M., Jun, W., & Ahmed, H. (2019). Effect of terrorism on economic growth in Pakistan: An empirical analysis. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 1794–1812.